The coming African debt crisis

A worrying build-up of borrowing

Africa has the fastest-growing continental economy on the planet. And the thing that has been growing fastest of all is debt—personal, corporate and government. In 2015 Africa and its boosters will start to worry that the debt boom is getting out of hand.

Sovereign bonds issued by some of the world’s most far-out “frontier” economies, often denominated in local currencies, are snapped up by hungry investors from Omaha to Zurich. In 2014 countries like Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire (less than five years after a government-debt default) and Zambia placed bonds worth as much as $1 billion, with all the issues oversubscribed. Kenya’s record-breaking sale of $2 billion in debt was oversubscribed four times over.

These government borrowings are in essence massive bets that the African growth story will continue. More betting will follow before the party finally ends—even Ghana, already deep in debt and with the continent’s worst-performing currency, had no difficulty raising another $1 billion in euro-denominated debt in late 2014. The African borrowing binge, which began in 2007 and has been driven by investors’ hunger for yield in the post-crisis economy, looks likely to carry on until interest rates and investment returns in the rest of the world start to normalise.

When that happens, Africa’s lenders may reflect on how history repeats itself—especially in a place with cyclical, resource-dependent economies—even if it is with a twist. The continent has been deep in debt before, and is in danger of a rerun. According to the IMF, in 2009 the whole of sub-Saharan Africa raised less than $5 billion through bond issues, including both private and sovereign bonds. By 2013 that had grown to $14 billion, and the 2014 total will be around $20 billion. Africa’s total debt-to-gdp ratio, which had fallen to less than 30% by 2008 (thanks to debt forgiveness as well as booming commodity prices), remains low, because GDP has been growing fast. But in some countries debt is now heading back up towards 70% ofGDP or beyond.

This time is different—and could be worse

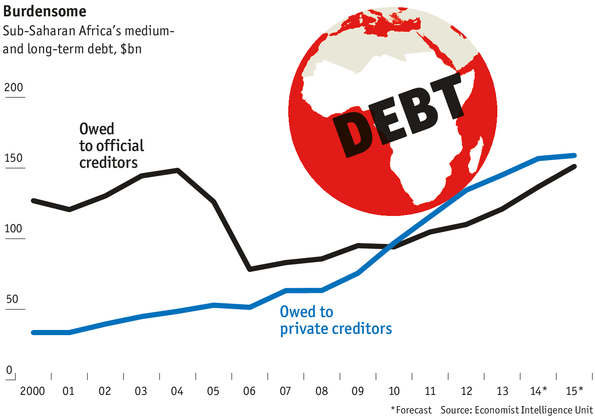

Africa used to borrow from official lenders: governments, the World Bank, the African Development Bank and the IMF. Today most of its borrowing is from private sources (see chart). Government loans and “assistance” are out of fashion. Instead it is private investors that are betting on Africa’s future ability to pay, with bond funds, private-equity and individual investors (including African ones) buying government debt. Private debt issued by larger African companies is adding to the pile; there have been large corporate-bond issues from Ethiopia, Mozambique and Nigeria, as well as from the traditional issuer, South Africa.

Corporate debt is usually dollar-denominated, making it hostage to currency fluctuations, though several governments, including those of Mozambique and Ghana, have recently had to issue bonds denominated in dollars instead of in local currencies. But the bigger worry for Africa is the nature of private lending. If governments get into trouble and need to reschedule their debts or borrow more even while they pay less, official lenders typically oblige. Private lenders are less forgiving.

When interest rates and long-term bond yields in developed economies rise—as they surely will, starting in 2015 in some places—private lenders will look on Africa less benignly. They will probably demand yields much higher than those that new African government and private bonds are currently paying, if they don’t refuse to buy altogether.

Much will depend on how healthy African government finances are looking. The signs are not good: whereas sub-Saharan Africa actually ran a regional budget surplus during much of the past decade, that has now turned to a regional deficit, as governments have spent heavily on salaries, subsidies and infrastructure even as commodity prices and tax revenues have fallen. Some countries, such as Ghana and Tanzania, are now running deficits of over 10% of GDP.

The world’s debt investors are willing to tolerate such figures as long as investment opportunities elsewhere pay next to nothing. Perhaps that will not change in 2015. It is also possible that African government spending will suddenly shrink. And maybe the commodity prices that Africa depends upon will soon boom again. But don’t bank on any of those events.

Richard Walker: freelance correspondent

No comments:

Post a Comment